Robin Sloan

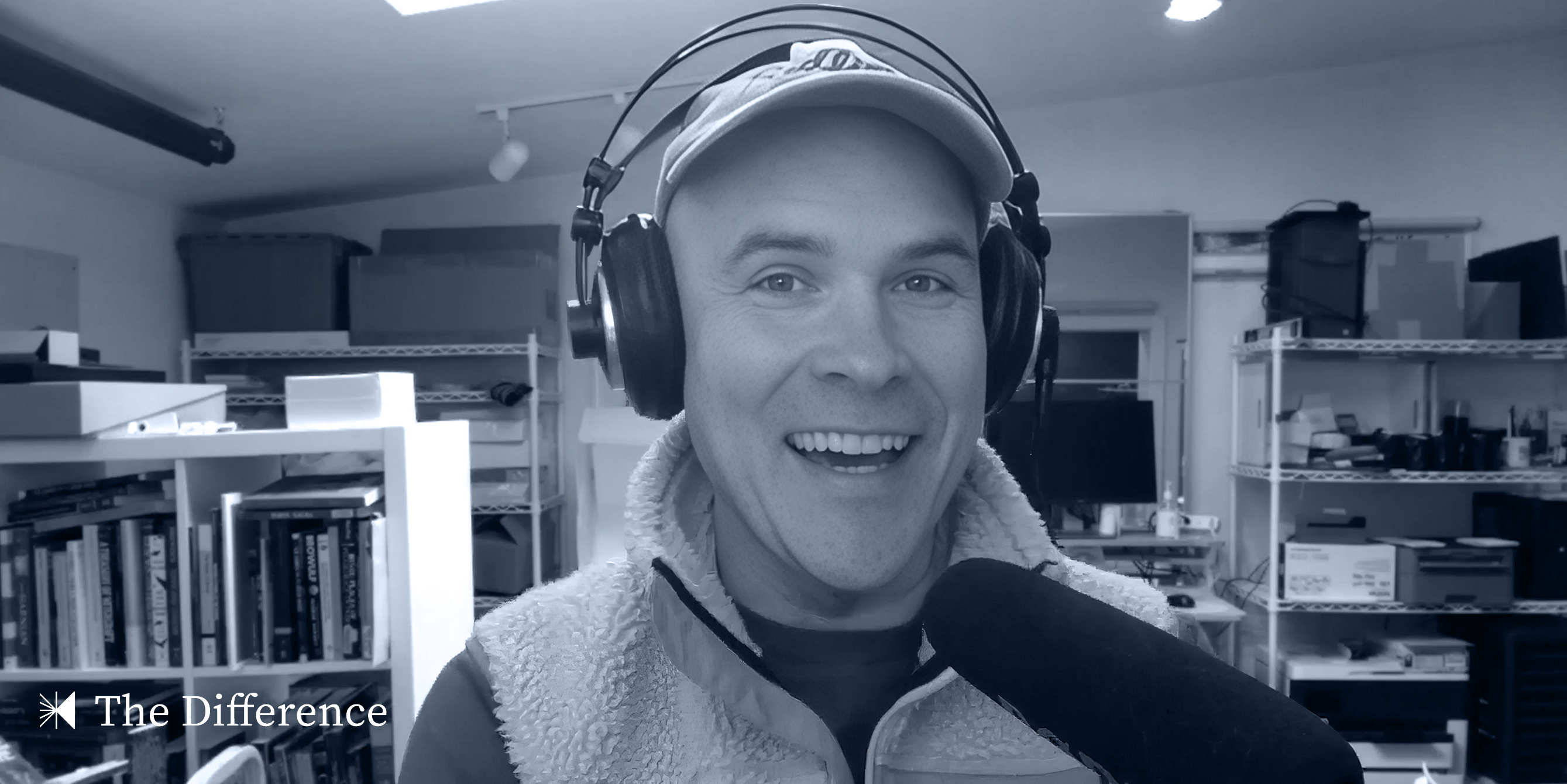

Robin Sloan is a man of many talents, best selling novelist, olive oil entrepreneur, AI experimenter, generative musician. We sat down with him in our first episode to discuss what creativity means in the age of AI.

- Published

- March 19th, 2025

- References

- Bestselling Author

- Early AI Experimenter

- Media Strategist

- AI Musician

- Olive Oil Producer

- Audio Version

- Transistor

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

Episode One

A Conversation with Robin Sloan

Part 0

Introduction

Paul Cloutier

Today we had a great conversation with our friend Robin Sloan, someone we've both known for many years. He's a novelist and a writer and has worked in the AI space for a long time. And he's a person that I could literally talk to for 24 hours, he's just an endless fountain of information. He's a super generous thinker and conversationalist and incredibly knowledgeable and able to bounce from idea to idea. At the start of this, I wanted to talk to Robin about creativity in general and what that means as we start to inject more and more automation, generative AI and these kinds of tools into the process. Is it still creative? What does creativity mean? What does it mean for us to think in partnership with these things? I think the conversation doesn't disappoint.

Kevin Farnham

Robin is such an interesting lateral thinker and so prolific in so many different ways. His mind moves quickly. so being able to get a chance to talk to somebody who is both utilizing AI in the way that he is and is somewhat of a skeptic is such a rare treat, I think, to be able to sort of not pull any punches and be able to talk in sort philosophical frames and creative frames and historical frames. an incredibly fun conversation. So glad we got a chance to talk to him.

Part 1

Over-relying on Automation

Paul

Robin is the bestselling author of Mr. Penumbra's 24-hour Bookstore, Sourdough, and now Moonbound. He's a technology writer and thinker exploring the intersection of tech and creativity. He's the creator of several experimental AI writing tools who worked with RNNs before you we were even working in the space of LLMs. He makes olive oil with his partner, Kathryn, at their home in California and throughout the Central Valley. He's an avid note taker and collector of ideas. He is a musician in the AI augmented band, The Cotton Modules with our friend Jesse Solomon Clark. And he recently wrote an essay called, "Is It Okay"? about AI ethics that received some great responses from folks on the internet. So Robin, thanks for joining us today.

Robin Sloan

Hey, thank you Paul and thank you Kevin. I mean, sincerely, just two of my favorite people and such smart, inquisitive minds. It's a pleasure to spend some time with you guys.

Paul

You've been a creator and technologist for a long time, and you've seen a lot of what is possible. Do you think there's an inherent tension in your mind between algorithmic creation and human creation?

Robin

Well, there's definitely some tension. I don't know if that's exactly where I would draw the line. And I don't know exactly where I would draw the lines. But to me, the word that kind of makes me pause more than algorithmic is probably something more to do with automatic. Of course, that's just the wild, the truly new thing in the last several years with all of these generative AI models is that where before, and as you guys both know and I'm sure many of your listeners know there's a rich, I mean, super interesting history of generative art, computational art, procedural art, algorithmic art. But it has always been a set of tools, know, and techniques being deployed by artists. And suddenly we do have this really weird thing of a big hairy computer program thats getting spun up that can just paint you a whole picture, kind of soup to nuts. So to me that seems where a lot of the attention is at this moment right now. But you know, again, maybe I'm overestimating it and actually everything old is new again.

Kevin

I do think you're right. It's a great distinction, actually, because I think that, you know, for people who are able to just sort of like, I need a picture for a thing, I'm now going to go pop this thing out the other side. It's not great. And so was just reading your blog post around this last night and thinking to myself, yeah, I can see the point of it for, think a lot of people though, and you know, this more than most, like using it as sort of an augmentation or an ideation space or part of the creative process makes a bunch of space, but the areas in which it's just sort of, I'm going to go automatically generate a thing, I think is a dangerous realm.

Robin

Yeah and as I think about this stuff, really, I'm always on the lookout for that sense of, is this something new on earth. And it could–it doesn't have to be a new economy, it doesn't even have to be really a profound new technology–it could just be a new feeling, you know? Sometimes you get that kind of itchy feeling of like, that's, that is weird, I never did that before. I never saw that, or I never knew somebody could do that before. And they're not even unpleasant feelings.

Paul, thinking back to the early, early days of my experiments with these tools. I remember there was a whole host of feelings that were sort of, I mean, honestly, they were pleasant. It was the feeling of, setting a little, by modern standards, microscopic scale AI model up to train overnight. my, my little GPU right, right in this room where I'm talking to you guys from would just be, would just be churning overnight. And the feeling was waking up in the morning and making my coffee and then logging in to see how far it had progressed. And if it had like, you know, learned anything overnight. And that was cool. I never had that feeling before. And for me that...

Kevin

Like Sea Monkeys!

Robin

Yeah, totally, exactly. Or, you know, maybe some, some mold in something you left you left out. Sometimes it was a little gross. Sometimes it was, sometimes it was disappointing. You're like, well, that didn't work. That was often the feeling. but again, just to say that like, I think having your antenna tuned for, the new, the genuinely new, I mean, that's a discipline that I just always try to maintain, and I think it kind of leads you in interesting directions.

Part 2

Cultivating Ambivalence

Paul

In your "Is It OK" post, which I thought was a really interesting take and approach to reconcile some of the ethics–maybe ethics is too big of a word for what you're wrangling with there, but just you know, a way of approaching what is the right way to work in this space, tangling with what does it mean to have trained things on everything versus on fewer things. I thought a lot of great questions asked in there.

I think it's worth returning to the article a couple of times throughout the course of this conversation today. I thought it was great to see this reaction from a few folks in counter response blog posts, which I thought was charmingly old school in the way of showing that that era of the internet still exists and still works that people were like, "Hey, I have a thought about this and I'm going to post on my blog about it!" But, maybe in a less charmingly new school way was this kind of like, "I have a take and I have to counteract that".

I'm just wondering maybe because everything is so politicized in the world right now, just your thoughts about well… I I felt like some of the responses to your your post were a little bit like, "I know this guy, he's like, he's a Bay Area tech dude". And they're kind of glossing over what you're actually saying by just responding to the like, I know what this is.

And so I'm just curious about how do you have nuance in these conversations in this era?

Robin

I mean, what I just insist upon for myself, for other folks who I like to read and who I really respect is actually, I mean, of course, nuance, but also ambivalence. And ambivalence is such a funny word. I feel like I say this for myself. My first thought, even now when I hear it, is sort of, know, middle of the road, kind of this, kind of that, kind of tepid, lukewarm. Of course, that's not actually what it means. know, the real, the deep, actual, true definition of ambivalence is having all the thoughts at once. So instead of, you know, a slider, if we have a, know, thought A and thought B and it's like a slider between them and you're like, yes, it's a, you know, half of each. That's not ambivalence. Ambivalence is thought A turned up to max and thought B also turned up to max and having, maintaining space in your head to recognize that like they both can be true and probably are both true in really important ways. I think it is a discipline. I said that word and I think it's true.

I think there are a lot of just casual forces in our world. The way people write, the way that people want to kind of converse in public space that really militate against it. want to kind of, you know, not to completely overload the analogy, but they want to take that kind of quantum wave function and collapse it down to one thing. Like, is it this? Is it that? Is it the other thing? And I think it's a really, you know, without, it's not, the intention is not to be weasely at all. It's not to...

It's not to avoid, you know, debate or argument or critique. I think it's just to insist that some of this stuff that's happening is so new and so rich and so complicated that I think the only reasonable response is one of like profound and like energetic ambivalence.

Paul

I think about it all the time because there's lots of things that I find worrisome or problematic or, or maybe also just kind of lame.

Robin

Yeah, let's not skip that some of the stuff just sucks. Or poor taste, right? It's like we talk about energy, we talk about politics and we should, but also, man, do better.

Paul

But you know, at the same time, there's parts of this where I'm like, I love this. There are things about, Claude, for example, like you can pry from my cold dead hands and to be able to balance this idea, this applied skepticism of I'm excited by this, and I love it. But I'm also very skeptical. And I think that's a problematically nuanced space to live in right now.

I actually, it did make me think a little bit in Moonbound, your most recent novel, and the beavers–basically a hyper intelligent race of beavers that are effectively running the world. The idea that there's a way of making decisions and being able to frame up each other's arguments. I know in other places you've talked about this inheritance from the Long Now Foundation of being able to, articulate your opponent's point of view before you can begin debating or arguing. And I think that's a little bit of what we're talking about here is like, how do you immerse yourself in this conversation without fully picking a side from the get-go?

Robin

Yeah, that's great. Thank you, Paul. Time to hyper-intelligent beaver mention in this podcast, approximately seven and a half minutes. That's the metric I'm trying to optimize in my life at this time. Yeah, that was, you know, and I just want to say, just to underscore, you know, boy, talk about the way ideas work in the world and kind of travel and can surprise you, those Long Now debates were an experience. Seeing real debates like that, it's just the discipline and the rigor of it. So it was like, electrifying at the time. That was years ago in San Francisco, where I know both of you guys have spent a lot of time and it's a place that means a lot to you guys. to have that kind of percolate and then land in the pages of this book, you know, now in the 2020s is cool. It just is a fun, fun, fun those loops of influence keep going.

Part 3

Productivity for Whom?

Paul

So, one of the other things that we've talked about in the past that is this sort of obsession with productivity that exists–you could argue it's really an obsession with capital or profit–but an obsession that exists within software development and tech and certainly within these models that we're talking about, whether it's Anthropic and, OpenAI. And I think everything is increasingly built for work or sometimes it's built for art. And I think the idea that we're freaked out about AI creating art–if thats even possible–because of the feeling of losing our humanity. And then on the other hand, what does it mean for these tools to do work for us? Which of course then we freak out about like our livelihoods.

And so I don't know, it just pushes me in the direction of thinking about a more hippie model or like shareware or these kinds of like homebrew AI models, you've on worked in in the past. I'm intrigued by this idea of a different way of going about this. Is that possible, you think?

Robin

Yeah, it's funny to say that. You've surely seen the meme sort of replicated and passed around where it was like, okay, the deal I heard was that the AI would do my taxes so I could go and be a painter. In fact, I have to keep doing my taxes and the AI is gonna go be a painter. What the hell? Yeah, yeah. And I do, I think it's like a lot of little jokes that make you chuckle. It's actually, of course, profound. And there are reasons for that.

The way this technology is all set up now, it's amazing. Again, the ambivalence. It's so potent. Even now, it's so potent, so protean, so flexible, and so incredibly limited and kind of broken in some important ways with the result that you have. Nobody with two brain cells would give any of these models the ability to make a consequential decision. Certainly not one that involved like, you know, large sums of money or people's lives or, or wellbeing or whatever. So as a result, all these amazing powers get aimed at stuff that kind of doesn't matter, or just, or just does not have those material consequences like art and jokes and I don't know, memes and, and weird stuff like that.

But to answer your question directly, I do think, I think there's a rich terrain of possibility for how the–I don't know what to call it–almost like the political economy of how AI plays out. And lately, and there's lots of examples of this, you see somebody like Adam Tooze, who's terrific, or Thomas Piketty with his deep kind of sociological, historical economic analysis from a decade ago or so, kind of bringing back the sense of political economy where you're like, actually, that's the right level of analysis. It has to do with like, well, what are the resources? What's the, where's the money? You know, and not just, not just, you know, liquid money, but, assets and chips and data centers and all that kind of stuff. But also where is the control and how is it governed and what are the rights associated with these things?

If I was in that kind of field right now–and I've said this often–I kind of can't imagine that every scholar in, almost every domain, certainly philosophy, certainly economics, certainly political economy isn't just focused on these questions around AI right now. It seems so juicy.

Part 4

The Homebrew AI Club

Paul

I often think of that weird little blip of an era that maybe went from like 1976 to 1990 or so of software development in the Bay Area and, you know, kind of all along the West Coast, that felt like more related to punk rock than business. It felt more related to this experimental art scene where people were making weird things outside of the scope of traditional profit-making enterprises. And I just don't know that AI got a chance to necessarily do a lot of that, at least in the kind of contemporary sense now. And of course you have some history there.

Robin

Yeah, don't give up yet, Paul. The arc of it is pretty clear and at least so far follows that sort of hyper accelerating trend. I remember well, it was around 2016, 2017, I remember Kevin and I had a coffee around that time, both of us just so wrapped up in these brand new emergent questions and possibilities. And one of the reasons it was so appealing to me at that time is that as you say, it was homebrew. It was the homebrew AI club, writ large I mean, and it was really cool. It was really, really fun.

Now what happened in short order kind of 2020 and onward is that the models got too big. Their requirements for data got too big. At least if you wanted to be sort of participating even remotely close to the state of the art, that suddenly it wasn't enough to have your little like rig in your, in your office here. You had to have a data center.

However, however, I, this is my little sci-fi prediction or possibility. I do not think it is at all out of the question that, techniques could change, the way we think about these models could change. And in fact, it could almost be like things that emerge as a result of the success and the hugeness of these data setter scale models, such that there is such a thing in the not so distant future as a little itty bitty model. And it doesn't know everything about like the exports of Botswana and the history of like, you know, the war of the roses. It doesn't it doesn't have all that.

But it has this reasoning core. And it does a lot of these interesting, useful things with language and with understanding, requests and prompts and stuff that we know these models do. And it could run on not only your home computer, but your phone or your refrigerator, your toaster, or whatever. That obviously raises a lot of questions. But the point is, it's not at all clear happily that the role for the amateur and the hobbyist is closed, at least not yet. And I think there's real hope for the future.

Kevin

It's interesting to think a little bit about. think about, don't know if you guys remember this thing called the cube. It was like this little blue box that was basically like a web server, mail server. It was all in one. It was bespoke to a bunch of different like general purposes, but it was bespoke, right? It was not a server sitting in a cloud. It was not a rack mounted thing. It was sort of like prosumer almost. And I can imagine scenarios where like, you know, I identify as whatever it is. I'm an artist. I'm a photographer. I'm a whatever it is. And I've go and purchase effectively some sort of like little to your point, Robin. Like, it's running in my background right now, but it's my data room, it's my stuff, it's my models, it's, you know, it's got some bespoke sort of guardrails on the thing, but right now the barrier to entry is still a little too high for those people to get in there. They're not gonna go mount DeepSeek into a box in there, like most people aren't gonna do that. But I don't think we're far off from the eventuality of having bespoke pieces of hardware in your house that help you to do certain things, and that will take a lot of time to inform, to your point, the refrigerator, whatever it is. But I do think that like it's just the next form of tools around that bespoke to how you identify your hobbies or your profession.

Robin

I mean, it's no question. just feel like anyone, you know, literally at any level of ambivalence around this stuff, anywhere on the sort of, you know, orb of opinion from the, harshest critic to the biggest AI booster. I just don't know who could disagree that that vision is better and more appealing than the centralized plumbing version of like, yeah, everybody is sending just, just blasting their little API requests endlessly to,

Open AI's data center and Google's data center and everywhere else. It just seems, you know, everything. It's, yeah, you know, exactly, exactly. It's, again, the dream of the internet, a decentralized system is still, you know, there's still hope for that. You do have to wonder what, you know, people, all the people everywhere, I mean, the taste and opinions of internet users en masse continues to confuse and disorient me. So I can't really predict what everybody wants. But I will say, and I think you guys know this well, it's been very fun and interesting to see Apple sort of stumble into this. They did not design this new architecture. It's not even that new anymore, the latest Apple architecture. They did not design that to be good at running local AI models because they didn't even exist at the outset. Turns out... Truly by accident, which is so beautiful, they are. And I think it's wonderful to see people kind of specing out their super turbocharged Mac minis expressly because they're going to let them load some of these models up locally and really have them entirely under their control. It's great.

Part 5

The Personality of AI

Paul

I've got like a feed of robotics equipment announcements that comes to my inbox, from having bought a number of like bits and pieces over the years. And the recent amount of basically machine vision, type camera sort of things that are bubbling up right now is wild. Like I got one the other day that was designed for plant recognition and it's a hyper, hyper specific. It's just a camera and a chip and it doesn't have any kind of cloud access. It's just designed to do this one thing really well. And you're like, I need a robot that knows what kind of tree this is. And I love that idea that it's not actually good at anything except for one thing. And it benefits from the larger, studies being done and model development and training, but really it only knows how to do this one thing. And I kind of love that. love these like, designing stupidity or ignorance into things almost so that they can be better at one thing.

Robin

There's a sort of, it's at this point, it's almost a cliche, but so a famous philosophy paper by the philosopher Thomas Nagel. The title is, What is it Like to Be a Bat? And the topic is about bats, but it's also just about like, you know, what is it like to be something different with different senses and a different, literally a different impression of the world? And it's great. It's motivated a million undergraduate PhDs to, or undergraduate philosophy students to like freak out in the middle of the night. But, it raises, and again, philosophers should be on this. What is it like to be a tree recognizing AI model?

I did get some insight into this recently. was riding in one of the Waymo self-driving taxis in San Francisco. And very, very smartly, I think they put this little dashboard in front of you in the passenger seat, giving you a rendering of the Waymo's view of the world. And it's nicely done. You guys probably have seen this. It's sort of these blurred sort of like polygonal forms and they're all kind of like cool colors like blue and green and you see everything it's you you see again it's confidence boosting because it helps you understand that the car like they definitely sees that truck or sees that person it seems that like person walking a dog and on and on–and this made me laugh out loud when I saw it–the one thing that's like a different color is a traffic cone. Traffic cones are represented in this dashboard as like bright orange traffic cone icons and they're either they just are like they're like shine like the sun. And you're like, of course, that's right. If you're a car, a traffic cone is like your God!

Paul

It's the native language of cars!

Robin

It's the most important thing. It's literally the most important thing in the universe! And everything else is kind of second tier kind of jostling, but you're like, a cone. And that, I think that's great. That kind of stuff, that whole like, you know, let's call it the emerging field of AI psychology. It's just great. It's fascinating.

Paul

Yeah, I also love the idea of displaying that type of information, because it's encouraging a kind of literacy amongst people as opposed to like Waymo or really any AI is a black box that is unknowable and therefore you must worship and it is magic. There is a kind of literacy that comes from seeing that stuff on that screen. You're like, I kind of understand what's happening, and I think that's a bit of an art form in the design of AI interfaces to sort of expose those underpinnings of what's going on at some level.

Robin

Yeah, I mean, I think that's right. And boy, talk about a growth field or something that ought to be a growth field. Precisely that the kind of articulation and communication of AI processes to end users, whether they're professionals or consumers or riders or passengers or whatever. I think it's restraining because I think it's actually it is now and will continue to be excruciatingly difficult.

I mean, people have remarked on this because, of course, there's a there's a whole field called sort of mechanistic interpretability. I know it's funny, I only know it by mechinterp. They all say, I'm into mechinterp. And it's about trying to understand the black box, trying to make some sense of how information is flowing through these incredibly complex programs. And they've made like a tiny bit of progress, but not much. And some of these researchers will remark with awe, the tasks set before like cognitive science researchers or people who try to study the human brain. Cause in mech and terp and in the world of this kind of AI understanding, you have access to the whole system. I mean, it's not that it's hidden from you. You can put these sort of software probes into every virtually every virtual neuron. All at the same time, you can pause it. You can rewind it. You can inject weird, you know, sort of signals like a brain researcher would kill to have this level of control of a living brain.

And they still can't figure it out. They still can't figure it out. So you're like, what, what are, I, you know, and again, the field has made progress. So I think, I think it is truly is like rich terrain and there's, there's great hope there and great opportunity, but I think it's hard. It's, it's gonna, and again, it's gonna continue to be hard to explain what's going on.

Kevin

Mm-hmm, you're right. There will be a lot of UI problems to solve there and human understanding problems to solve there that are definitely rich, rich places for people like Paul and I to double down on.

Robin

Yeah, I think that's right. mean, again, sort of in terms of both just a big open space where the work hasn't been done yet and also one where even small measures of progress would mean a lot and would count for a lot. don't think there's actually too many fields, certainly in the realm of kind of technology, that have those properties right now.

Part 6

What Even is an Image Now?

Paul

So returning to creativity a little bit, in in "Is It OK?", you had a fairly strong point of view about Midjourney and Dall-E and some of the image generation software as being kind of lame and maybe even problematic, ethically speaking, whereas less so for code generation. And I can sort of understand or see code is maybe more factual and perhaps, has a structure and that makes it less subjective versus images, which are clearly subjective. So does that suggest that code isn't creative or does it suggest that there are actually types of creativity that are okay to automate? What are your thoughts on that?

Robin

Yeah, well again, I like I said, automate, because I think that automatic part of it is really, really key.

No, so it's for sure not the case that code is not creative. Super, super duper creative. mean, sometimes I think really, really good, interesting code shares more in common with poetry than with anything else, you know, in its elegance and compression and like, oh, I see what you did there. Wow. So hyper creative.

For me, it's actually kind of two very particular things about code. One is, if this were not the case, I believe I would have a different opinion, but it is simply the case that open source code for not like a few years, but for a long time, for decades, has just carried with it the expectation of a rich and very surprising reuse. Everybody knows when you post open source code, people will use it. And obviously there's different licenses that demand certain things, but under most of the conventional licenses, people are going to use it to do things that you never expected. And that's just the way it is. Because you yourself have benefited from those tools and those resources and those offerings yourself. That's one part. The other part is a little subtler. I think people could disagree about this. But although writing code is extremely creative, code itself is never what people consume. You don't visit Google and read the source of the web page. like, good. Thank you. You solved my problem.

No, you use the thing. It's this intermediate product. It's almost like the, I mean, I don't know, it's the gears inside the watch or something like that. And to me, it just buffers the feeling. And I guess it in some ways does mean that there's still always going to be this, maybe not always, but often this human architect or this larger frame in which, yeah, this AI-generated code sits as this kind of ingredient.

Whereas, you know, if yeah, Midjourney makes the image, that's it. That's what they're showing to people. Or if, you know, Claude writes a news article or something, and then they post it online, that's, that's the final thing. again, I, maybe others wouldn't find that difference. It's quite so meaningful, but, for me that, that little extra distance, seems to, seems to

Paul

Some of what you're responding to there, I think, is this sort of permanent, like a finished state versus code, which is a kind of interpretive ongoing thing. You're running it to make something happen.You've talked a lot about the Rise of the Image, Fall of the Word, the book, as like a kind foundational text for you at one point. And this idea that culturally we're shifting our way of processing things and understanding the world in this more image and media based way vs text.

I think we still have this idea that an image is a finished thing, that an image is a fixed construct. Whereas I wonder as things evolve to be more interactive, more interpretive, more changeable, does that change a little bit? Where you're like, you're actually creating the rules for an image, not an image. And that image changes and evolves over time.

Robin

Maybe, maybe. It makes me think, and I'm sure both of you have had the experience of generating an image around something and you put in the prompt and you kind of go, that's not quite right. And maybe you actually just roll the dice again. Maybe you don't tinker with anything. just, know, cause again, it's, know, with a different random seed, you get something different and yet, and yet it's not different. I, I, again, I think my undercurrent, my overarching theme is I just want the scholars to go crazy on this stuff and give us some insights we can work with. Because I want like an art critic to look at the thousand generations for a given prompt by Midjourney and write about how, I mean, yeah, they're technically different, but somehow they're also all the same. They really are. There's this sort of like, they all have the same, even if the pixel distribution is different and a hand is raised in one and lowered in the other and the background is cloudy in one and full of jagged lightning in the other and all this kind of stuff, they have like exactly the same information content.

To your point about what is an image, I guess the answer is I feel like five years ago I knew, and maybe I know less now.

Paul

The artist that I think tangled with this already is Sol LeWitt. You have like a guy who basically defines rules for how to create his art. And then in many cases gave it to a museum and then they created the art based on that. And I think like this is from the sixties on, like there is already a precedent for this idea of rule-based image generation that exists within here, within this scope.

Kevin

I also think there's a huge spectrum within this, right? Like there's always, there's a human in the loop somewhere around this, whether it's at the prompting level or you're using models to do discrete little pieces of it. And I think this gets more complicated over time and more nuanced over time. And so it's not a binary operation. It's not like we were talking about before where it's just automatic where I need an image and here comes the thing. You're using tools in different ways. New tools will be invented. It's not exclusively the realm of one image model or another. There's combinations of things and it's just the natural progression of tool development that sort of marches us in a direction.

Robin

And it is, you know, this maybe sounds a little old fashioned or, or I don't know. It's not like something you even want to talk, you talk about in the 21st century, but I do think it comes back around to taste and to insisting that people that people like actually only share things they're proud of. you know, it's the word, of course, the great, the great emergent, term for AI generated garbage is slop. And it's so good. It's just whoever came up with slop deserves a Linguistic Nobel Prize. It's the perfect word.

Paul

It was Claude, sorry.

Robin

The twist, the twist!

So, of course a lot of these problems, these problems of political economy, they're human problems at root and you can kind of trace it all the way back. Can you go you go all through all the laws and the rights and the economics and whatever, and you find a person who made some decisions or declined to make some decisions. And I think we are all allowed and maybe even encouraged to say, what the hell, man? You know, like it's up to all of us to actually make things and produce things and share things and publish things that we think are good and worth other people's time. And when people fail to do that, it's, yeah, they deserve to get razed.

Part 7

AI is Missing Some Flavor

Kevin

One of the things in your article, your post that held my attention a lot was this, the idea of umami. You know, there's something in there and I can't quite reconcile what it is and why that sits with me every day now. So you're living rent free in my head since I read the thing. But there is something there, right? Where it's like, maybe it's just, and back to your point of philosophers, like this is just the humans perceiving and feeling something about that thing because of the human in the loop moment.

Robin

Well, I would, again, it's rich. It's cool, right? For as distressing as many of these challenges and questions are, they're also really, really interesting to think about and to tangle with. So this is not the whole answer, but I do have one suggestion. I will expand my domain in Kevin's brain by just a bit, I'll make a little shed, a little shed in the backyard…

Kevin

Yeah, I'm gonna have to charge you more rent.

Robin

Which is that, of course we know that just literally the mathematical programmatic way these models work is by, creating this probability distribution in hugely high dimensional space. You can't imagine, you can't hold in your head. But it's not completely far off to imagine it as a big fuzzy cloud, one of those Gaussian point distributions that we know them in 1D and 2D and maybe even 3D, but this is like a jillion D, but still it's that fuzzy cloud and the most predictable solid, yeah, that is just a picture of a guy. That's right in the middle.

And then maybe somewhere at the edge, there's like a really weird, you know, maybe it does, maybe it evokes kind of a Saul LeWitt, you know, know, installation or something. And, and again, there's weird stuff and strange stuff way out of the edges. But I think the umami often that we sense from human work and really good, meaningful human work is that it's actually even a little further out. And maybe not the whole thing. It's not like I'm not just talking about only avant-garde, super bizarre artwork.

Maybe it's just a piece of writing or even an email that somebody sends or something. And just one part of it is like kind of weird. And it's, you know, just a re it's, it's idiosyncratic, it's personal, and it's just something that like nobody else and no other machine in the universe would ever do. I think that's fresh. That's the thing that often we as people respond to. And, and I think interestingly, it's kind of the one thing that these models for all their power almost definitionally cannot do.

Kevin

Interesting to think about it culturally as well, because if you listen to trend identifiers culturally, especially amongst younger generations, you see the swing happening really quickly to the things that are more human, more bespoke, less corporate, less all of these things, sort of swimming away from the automation and all of the things that are happening to things that are hand-spun, to things that are community-focused. It's very, very interesting to watch the the pendulum swinging in the other direction rapidly, especially amongst younger people.

Robin

It's, mean, again, we can, we can hope, right. And one hopes that that's not just a sort of, you know, relatively contained nostalgic, bordering on twee movement, but actually could stand in for something larger. I mean, I think Paul knows this best because we've talked about it often. I'm such a champion for the, for the physical, especially when it comes to economics. I mean, it is simply still the case that, making money in a purely digital environment is basically impossible unless you're operating at just eye watering scale or doing something incredibly valuable and specific, you know, for a very particular group of people that will pay for it. Whereas, and like, you know, living in that realm, operating in the digital for a long time, you might have the assumption, man, it's hard to make money. It's hard to run a business. In fact, it's not. As soon as you toggle back to the physical,

You're like, oh man, I could sell this loaf of bread for $5. I can sell this tin of olive oil for $30. Oh wait, how many do I have to sell to make? Oh, not that many, you know? And so that sort of, I actually think it's, you know, it would be wise for the youngsters to embrace the physical, not only for the spiritual aspects, but you know, so they could maybe pay their rent in the decade to come.

Part 8

Woe, Unto The Robots

Kevin

It's a great segue, by the way, into what you, the other thing that you do. I'd love to hear you talk a little bit about your journey here with olive oil. It's just an incredible vector through your life.

Robin

Yeah! It is, and what a great surprise. Boy, yeah, the thing I always tell people about the olive oil, especially in its incarnation is some of the stuff that's gonna be the most important in your life is just gonna be totally random, not part of the big plan, not part of the, yeah, I this vision. No, it just was, it lands in your lap or maybe it lands on your head and you're like, okay, let's see where this goes. Yeah, so yeah, in addition to all the tech nerd stuff and the writing stuff, I help operate a small extra virgin olive oil producer here in California with my wife, Kathryn Tomajan. It's called Fat Gold and we operate here in Oakland and we also have a mill, an olive mill in a facility down in the San Joaquin Valley near Fresno. And I will say, mean, this guy, just, you hate to sound cliched, but sometimes the cliches are true. It's such a physical task.

By the way, sidebar, and this can sound like a joke, but I truly believe it. Everything else will be automated and roboticized, you the year will be 2075 Everything will be taken over by AI and the last Human task left standing will be olive oil production because when I tell you that this is a finicky physical slippery Process I I woe unto the robot that tries to that tries to do this job So that gives me that does give me some it gives me some confidence.

And, again, it is very physical and for somebody, you know, and I know this, this resonates with, with you guys too. I spent a lot of time, you know, on the screen, I spent a lot of time in my own head. I spent a lot of time stringing words together. It's all the realm of these sort of symbolic abstractions and to have something that insists on the, the calendar of the, of the seasons, you know, and the, just the, you can't, can't stop the physical world from, from rolling on and also, and also makes demands of your body to move in space and lift things and dump bins into other bins and pump oil from one tank to another, know, all that kind of stuff. Um, it's just been a great tonic for me. I've learned a lot about whole other parts of the world. and, and, know, it germane to just the general question of thinking and getting ideas and

And honestly, to talk about that blog post, the "Is It Okay" AI blog post, I thought about that post a lot over the harvest season, just this last fall, you know, October and November. You're busy, but you know, sometimes you're also standing around and it's, I've said before that sometimes at certain times of day, running the olive mill is like a giant version of washing the dishes. And you know, like famously washing the dishes, you have the best ideas because you're just like there and you can't look at your phone because your hands are busy and your mind kind of just starts to spin and it's like, it's great. It's such a, can be such a generative time. And really, and honestly, the, the, the milling work is often like that kind of even bigger because it's literally a bigger machine and, bigger stretches of time. So I took tons and tons and tons of notes, little, little scraps of thought, just as, I was wrestling with, with these questions myself. And then, you know, lo and behold, I got some time to actually write it down and post it. And what a cool, what a cool, you know, cycle to be able to inact.

Part 9

Embracing Seasonality

Paul

I love that idea of seasonality in there too, that software design, technology, et cetera, doesn't have seasonality, And so this idea that there's a sort of break that enforces you to take a little bit of time back, time away, obviously some people take sabbaticals or whatever, but it's always so that I can be more productive instead of I'm just going to go be someone else and do something else. You're going to always come back with something new and a different perspective.

Robin

That, that honestly was such a surprise to me. Never imagined that my year would have that structure. And, yeah, I'm, I'm grateful for it. It's, it's turned out to be. I always, yeah, I avoid saying productive because I, that's, I want to, I want to be precise. It's not, productive, but I mean, I think maybe generative is the word it, it, creates new opportunities.

Kevin

It's interesting, think, as A, we get older and B, because we all live in such abstracted sort of mind spaces, to be more present around the passage of time and through that seasonality is so interesting. know, I do, I've been sort of dabbling in permaculture over the course of the last several years and you really start to think about nature and nature cycles and the relationships of permaculture to other vectors in life. it's really a fascinating thing to take in. Plus, it's good to go outside and get a little vitamin D and all of the rest of those things, right?

Robin

It is good to go outside. It is good!

Kevin

But it does really help to frame a little bit of the passage of time in more meaningful ways, which can be very elusive as we get older, especially during the pandemic, just like, what the fuck just happened? Like, how much time just passed? Yeah.

Robin

Yeah, yeah, what year is it?

You know, and also I would say that this kind of implicit in what you're saying there, Kevin, part of that is a recognition of the things you don't have control over, the passage of time and the seasons being one of them. You know, there's a lot of people in California and in Europe who, if they could, would magically make olives produce fruit, every month of the year. And I'm sure some have tried, you know, with weird gene editing, but you actually, can't, you can't. It's just, this stuff is, it runs the way it runs. The year evolves the way the year evolves. so it sets your calendar of work and business in this just absolutely immutable way. likewise, things grow, things die, pests sweep in, and you're like, oh man, where'd that come from? I…

Paul

Guess there's no carrots this year.

Robin

Yeah, I guess there's no carrots! And that humility and flexibility. is, mean, obviously just a good thing to inhabit. think there's actually probably some connections there to perhaps how we'll have to think about and relate to AI because you know, it's not, it's not the, you think about that sort of high modern, vision of, of engineered. You know, precision engineered, perfectly controllable systems. I mean, I think, whatever it could be a jetliner or a Mac book, the modern Mac books, like what a, what a absolute encapsulation of the high modern relationship to the world and to work. And it's great. Permaculture is not that. Olive oil is not that. And I kind of think that AI is not that either. I think it's going be challenging for a lot of people.

Part 10

Gardening vs Crafting

Paul

Some years back, I think it was related to music, and we'll get to that in a second. You had a quote, and I'm just paraphrasing here, but it was that creating with AI has a lot more to do with gardening than say carpentry, where you're not creating an object, you're creating conditions in which an object can evolve or a thing can evolve. And I think about that a lot, this idea of gardening as an approach to design. You're really designing rules.

Robin

Yep, that's right. That's exactly right.

Paul

You're designing conditions, you're creating bounds in which randomness can occur and like embracing the randomness and accidents versus–say–craft in graphic design and communication design, where there's the grid and there are clear rules for how you do it. And maybe certain people break the rules, but fundamentally there is this like, there's a right way to do things. And I think these approaches are not at odds with each other because you can kind of get there by putting them together.

But I find that really interesting, you know, that there's different ways to approach this.

Kevin

A very compelling way of looking at it, think, as well. And it is related to permaculture a little bit. To that point, Paul, like that you're sort of then watching and witnessing and taking in how things behave once those rules are in place, being more observational around things and understanding how it plays into a broader system and the effects. I see it's very, very directly related. It's a great way of phrasing that.

Robin

I mean, again, the humility is in some cases, it's quite breathtaking when you recognize that these companies, I mean, they're so young, but they're already so big and so rich. Think of your OpenAI's, your Anthropic's, whatever. And of course they're constructing these, programs, you know they really are just computer programs that they're charging a lot of money for. And they're so valuable, you know, if they were to be acquired by some other company would be billions and billions and billions of dollars.

Kevin

I mean, losing a billion dollars a month is hard work.

Robin

Yeah, you gotta work hard at that!

And then to add, they're just like layered up, they're staffed with just some of the best, like most hardcore engineers of all time from all around the world. And so you're like, surely they must be like programming those programs. And it's like, no, no, they're not. What they're doing is, and I use this word, I came across this word in my own thinking, and I put it into that post and I really like it. I think it's artful, but I actually think it's also very precise. What they're building in those data centers and with all the code that they, that they do write themselves is a trellis. They're building this big complicated trellis, but that by itself, you know, they could finish that and it could be done but it doesn't do anything in the same way that a trellis is not a rose bush or really an anything. And then they do, they, there's that important crucial next step of, well, let's let it grow.

And you know, what's amazing also is that that process, even running at computational speed still today takes seasonal time. I mean, they, they create that trellis and then they start the growing process. And in some cases they have to wait months to know if they've succeeded or not, or to what degree they succeeded. All that stuff is just, just delicious. You couldn't, you couldn't make it up.

Kevin

Right. It's pretty ripe for allegory and flowery language. Just to double down on the pun.

Part 11

Biology is Totally Freaking Weird

Paul

Well, it also kind of makes me think back to, when you mentioned Nagel earlier, and the What is it like to be a Bat essay. And I think a little bit about in Moonbound, you have like the narrator, the chronicler, you know, is an AI basically evolved from partially from yeast. I love this idea. I love the idea that there's like some other type of intelligence. you know, yeast are like–notably they consume sugar and produce alcohol. That's their primary purpose. That's their only real, basic mechanism. so like, is that their logic gate? Does it color the way they think about things? Did you think about that when you were writing, was there an aspect of how would an AI would have evolved differently from the way we're currently doing it? Would it would approach the world and learning differently?

Robin

Totally, I mean I thought about it. I can't say I made much progress or had much success. I think it's a very hard thing to wrap your head around in any, in any way. The, some ways, I think the thing to do is, to try and not figure it out. Cause I don't think we can. there's a phenomenal book, highest recommendation, called How Life Works by Philip Ball, relatively recent book and–hey, it explains what it says on the tin, how life works. In particular, he brings together a lot of relatively recent research that, at least to my eye, has not made its way into popular understanding and the popular consciousness. As a result, what he reports in it, he talks about all different scales, ranging from the genetic to the molecular to the cellular, the whole macro and micro world of life. Baseline, it's totally freaking weird.

It's weirder than you think. It's weirder than anybody ever thought. It's so hard to analogize or to find analogies for. And in fact, one of the things that this is what made me think of it. One of the things that Ball wants to do, he says this in his introduction is, you know, we note that for decades now, the analogy, sort of the, you know, metaphorical language for life has been machinery and has been machined based, you know, and you can just go for all like the DNA is the blueprint of the cell and like, you know, the mitochondria, the little generators and on and on and on and on and on. And he says, first, it's not the analogy doesn't work. It obscures more than it reveals. So first give that up. But then the second thing he wants to say is, there is no analogy. It's actually so weird. And so exactly itself that the only analogy for life is life and sorry, man, you got to just learn about it. And I I found that really kind of bracing and challenging. And, then the whole book, I just felt like my brain was on fire. It's fabulous.

Kevin

Yeah, another book that I would recommend it sort of in the spirit that I can only read in short doses and I just need to put down and just like kind of live with for a little little period of time is this Ways of Being book by James Bridle. I don't know if you guys have seen that thing but that book really it's really warping my view of intelligence. And I think there's a lot of

Robin

Yes, absolutely.

Paul

Yeah! That book was actually the inspiration for this question of what it is like to be yeast.

Kevin

I really liked his point of view.

Robin

Yeah, it's great. It's really, really great. Notably, what I love too, you guys might or might not know this about James Bridle has had this incredible, wonderful arching career started off as kind of a, I would say sort of a web person with a real interest in books. It was kind of like books and eBooks. And this is maybe like the 2000s, early 2010s, but then started taking art, like really like kind of public art and fine art a lot more seriously went on to do all of these wonderful interesting installations that kind of commented on like, you know, autonomy and drones and, and, and computer vision and all that kind of stuff. And now as I understand it, I believe this was true at the time that, um, he wrote ways of being at least he lives on a Greek Island.

Kevin

Yeah, it plays a big part in the beginning of that book.

Robin

Right, you're just like, James Bridle, you did it, well played.

Paul

You got it figured out. This is the Way of Being.

Kevin

It's pretty great.

Part 12

Creating a Language

Paul

So we're really all of us designers in varying ways and care a lot about design and typography. In Moonbound, you created a typographic script and really a language–Sakescript–which you sketched a lot of it out and then worked with a typographer to define how it would work as a font, and you're thinking a lot in the book about like, the sort of epistemology of how people think and how, creatures think and all, and language affects the way that we think and express ourselves. Did designing a language or at least a typeface or script change any of that? Did you have any indications that based on this type of writing that there is like a different way to think or express yourself.

Robin

That's a good question. Maybe not. That would be cool if I could say yes to that. Yes, Paul, my brain works differently now. No. But I will say it was almost the inverse. The primary motivation for the script was to play in the JRR Tolkien sandbox, obviously. It's sort of genre within a genre. There's fantasy and science fiction broadly, but then there's the fantasy books where there's some weird letters on the page and you go, ooh, what's that? And so I just know to be totally candid and straightforward, the primary motivation was to be able to have that kind of fun and hopefully produce that kind of fun for readers.

However, being a good world builder, you don't want it to be completely random and unconnected, you want it to mean something. And so I basically had to frame it up with a series of questions like, what is this for? What is it not for? And what I came up with, is totally connected to what we were just talking about.

This is the language, the script system really of the wizards. in my strange warped far future wizards are masters of biology. They have these wild, inscrutable biotech labs and they can remake people's bodies and do all sorts of weird, interesting things. so I knew this was going to be the script system they used. I imagined it cascading down there like you know, inexplicably cathode ray tube screens, just, cause you know, obviously that's the way it's way cooler. So I imagine these like strange glowing screens and these, these characters cascading down, but that, that leads you down some interesting paths like, okay, well what, what kind of writing system would be suited to that?

For example, one of the things I struck upon early is that there would be 21 characters because there are 21 essential amino acids that are the building blocks of all Eukaryotic life and you're like that's cool. What a great resonance. So it's not it's not you know, just some random number It's certainly not the 26 of you know, the Latin alphabet. It's something different, something that's linked to this real thing in the world

I recommend it particularly to anyone who is already interested in fiction or world building, it could be for a comic book or a video game or anything like that but I actually really, really recommend the exercise of creating a fictional, some kind of fictional language or, or script or oral. It could be written, whatever. definitely activates not only parts of your brain, you probably haven't used, but kind of like all of your brain at once. And it's for sure one of those things where it begins to inhabit your dreams as well. It's just one of those great, like that little flywheel gets going. And for me, it was a few months of like, I would just see the the shapes kind of missed in front of my eyes.

Paul

Yeah, I think about like The Arrival the Denis Villeneuve movie and how the typography or whatever language or script they created for that and how much that that's rooted in a literally alien type of brain in terms of how you express yourself. And I'm always intrigued by like the idea of how you express these things that are not understandable by the human mind or at least the current human mind.

Robin

Yeah. And again, I think that kind of question is even, I mean, I guess I don't know if it's even answerable or not, so what? To tangle with it, to kind of face up to it and just let it sit in your brain for a while. I actually think there's a lot of people out there who really shy away from that kind of stuff for a variety of reasons. It's almost kind of like looking at the sun. And to have kind of the curiosity and also the courage to just, to just sit with it for a while. I think it's a really healthy exercise.

Part 13

Creativity With the Machine

Paul

Yeah, it creates a kind of empathy that just even accepting there's an unknowability is probably healthy for you in the process of creating things.

So you are also a member of a, what I sort of think of as AI augmented–I'm not sure if that's the best way to describe it–A band called The Cotton Modules with our friend Jesse Solomon Clark. Talk a little bit about what it's like creating music with AI and to what extent that works. Is that different than writing? You've described writing with AI as being kind of boring, and this is not that.

Robin

Yeah, it's totally, totally different. It is so funny, we embarked on the band project a few years ago. So obviously it was a different era because it's everything is moving so fast. Referring back to Umami, we have two albums, but we actually used the same model or I should say I used the same model because I'm the AI wrangler part of the duo. I used the same model for both of them. At the time of the second album there were newer "better models", but I didn't like the way they sounded as much. They were smoother and cleaner, thought they were a lot cheesier. Whereas this older model, this frankly more primitive kind of approach was from way back in 2020. It was the hot release back in 2020. And, Jesse and I both agreed that it was precisely It has overall the kind of sound of like a FM station you've like barely tuned in somewhere, which obviously just to say that and imagine that that's like so evocative and so cool. It's not hi-fi. It's not even in stereo. But the sound of it, the actual, and this is so often the case, the way it made mistakes, the sound of its glitches and the sound of its imperfections were precisely what drew both of us to it.

So, and that's all to say, not only does it sound kind of screwed up, it's also incredibly slow and painful to use! You're like, so this must be a real like efficiency, you know, productivity improvement over like producing music. And you're like, no, no, this is a terrible idea. No, this is far worse. We'd be way better off just just, you know, dinking around on a keyboard and opening up Pro Tools. But but…

You know, it seemed to us that the effects we could produce and some of the sounds that I squeeze out of this thing were, you know, interesting enough to make that worth the labor.

Paul

Well, that also makes me think a little, we're both fans and users of the Risograph machine, the Japanese screen printing machine, for lack of better term.

Robin

Yeah, I sometimes call it an automatic screen printer.

Paul

And, you know, it makes all kinds of mistakes and it's not really optimized for perfection. It was originally built for like basically a glorified mimeograph machine. You know, the registration is often weird and the colors are not perfectly reproduced every single time. And there is something kind of magical about that. And I just sort of wonder when I think about, you know, to the point we've talked about this a number of times today, this kind of like embracing the randomness of some of this and designing for the randomness. sort of think of designing with AI sometimes as being this like shambling reproductive intelligence. It sort of gets there by throwing random stuff at the wall and seeing what sticks and what works and eventually it sort of gets there. I think some of this is, as you said, the novelty of folks trying to reproduce this accidental stuff, but there's also a little bit of a like a contemporary approach that asks, how do we recreate the randomness in all of this?

Robin

Yeah, I mean, I think this connects back to what Kevin was talking about the sort of this new hunger, perhaps, for these for these analog systems. And you can ask the question why, and I think part of the answer is precisely because of their signature imperfections, not only in and of themselves, but what they kind of said about the world around them.

You know, the Risograph tells you it is an analog printing process. It really announces it. It is like, no, this is real. This happened in the real world. When you look at one you can't help but imagine the person using the machine and them coming out with these layers of ink. Now I contend that everything has a grain. There's no such thing as a grainless medium or a perfectly smooth inner medium. It just doesn't exist. And I think it's interesting to ask… what is the grain of AI?

And that you could ask the question five years ago, you could ask the question now, you could answer that question in another couple of years. I think the answer, at least in part, is smoothness. Smoothness, smushiness, slipperiness. And I think we see this in the art. It's not that AI art generators can't make a straight line or a sharp border. But I kind of think they don't like to.

Obviously part of that is Midjourney's own kind of tuning and creating something that they think a lot of people will like. But it's also recognizing where the technology kind of wants to go and leaning into that. And so what is AI's grain? It's this sort of smooth, glossy, luminous. I mean, it's very Thomas Kinkade, I think, actually. like the really, it's got a real, you're like…

Paul

Ooh, that's perhaps the most damning thing you could say.

Robin

Yeah, I know, yeah, yeah, I meant it. I meant it as a slur.

Part 14

The Grain of AI

Robin

So that's just all to say one, the AI stuff has a grain and recognizing that and just as you would with any other medium, deciding to lean into it or against it or counteract it or accentuate it, super important choice, both technically and creatively. It does, I would just add, it also creates this sort of unsettling specter of like art 15 years from now that's like some future technology. And they're like, yeah, well you make it like a retro AI thing. Let's make it look like, let's make this poster look like Midjourney from like 2025.

Paul

Yeah, totally. A hundred percent!

Kevin

Give that guy six fingers!

Robin

Wouldn't that be so funny? Yeah.

Paul

Yeah. Nobody wanted VHS artifacts, 20 years ago, but now we're putting VHS artifacts on everything.

You mentioned the straight line thing, that AI just doesn't really know what a straight line is. All it knows is what has occurred before. And I do think there is this sort of like Chain-of-Thought evolution that's happening in AI where it actually can know what a straight line is, where they're adding these kinds of physics models. And it is interesting to consider, as a designer, what does it mean to create these intermediaries in the model where you're like, all right, this is what 1960s graphic design is. And not just like, this is what it looks like, but these are actually the rules that define it as part of a process. So you're training in–and I don't know if that's good because again, that feels like the most kind of rapacious version of this where we're like, we don't need people at all– but you're training the intelligence into it, not just the happenstance of it.

Robin

Yeah, yeah, yeah. You guys are going to like this, I think. I don't know. Just kind of push your buttons. There's a wonderful, wonderful AI researcher and pioneer. It's funny, I know him mostly by his old Twitter name, which was Hard Maru. But his real name is David Ha. And he's been working on this stuff for a long time. And I don't actually know what he's up to right now at this moment. But for quite a while, and primarily, think, at Google, he was working on AI models that, instead of moving pixels around and understanding the world in terms of this big smear of pixels, it was focused on the line art, and, reproducing line art in a really, in a really parsimonious way. And his argument was, again, I don't know enough to be able to evaluate this is right or wrong. I do know that I just always loved it. His argument was you have to really understand the world in order to make a really great line drawing because a line drawing, it actually, it like derives it's it's pleasing nature from a sort of parsimony and a like, yeah, no, I know what this object is. It's not just like smear of pixels that satisfies constraint, but instead like, no, no, no, I know the shape of a dog and that tells me that I can use these four lines to like create the incredible impression of a dog. And I just always thought that was very charming. I want that to be true.

Part 15

Scientific Progress with AI

Paul

So in your article, you were asking about these kinds of almost red lines that might make it worthwhile to consume all the information in the world. It might be worth it if we made significant scientific breakthroughs. And I think often we tend to treat AI as bit of this magic box–AI will figure this out. And I'm sure that there are opportunities to create sort of super scientists that are good at parsing every article that's ever been written and finding hidden patterns and all of that. But have you seen or are you tracking different models? One specifically comes to mind that sort of teed this up for me, which was there are a number of products that are being designed right now that are about simulation, sort of agentic simulation where you're like, let's create a bunch of molecules and let them go and evolve, but then let's also layer on previous behavior on top of that. And it's not really a LLM based prompt based thing, it's something new.

Robin

Yeah. And to be clear those models, and you think of something like Alpha Fold at DeepMind, know, which has been huge. mean, it's not, it's not perfect. It can't predict everything with perfect accuracy, but most people in this field of kind of protein folding will basically agree that, that Alpha Fold substantially solved this problem that at best was considered still a totally thorny bag of monkeys. And at worst, maybe unsolvable.

So there's that and a bunch more stuff like that. To be clear, I think those models conveniently, know, happily don't raise any of these ethical concerns whatsoever. I don't think anybody has some, you know, moral stake in like, "but all the protein geometries! You can't scan that. You can't train on that". No, please train on it.

So I think that my big question, is it OK? And this sort of the moral encumbrance that has largely to do with the commons and like the disposition of the commons. I think it only applies to the language models.

However, I think it is also the case that some of the brightest hopes, certainly held by the most rah-rah boosters of this kind of stuff, are attached to those language models. They are imagining not merely super powerful tools that will empower scientists to do really, really incredible and helpful things.

I think it's interesting for people to kind of know this and hold this in their heads. The model, and really I think a lot of the hopes for a hypothetical AI science are bound up in the figure of someone like a Paul Dirac. And there's–among physicists and all kinds of scientists–a whole range of different ways they've worked and uncovered things about the world.

There's some that just sat at a desk. It's incredible. And it's incredible that anyone, any mind actually could ever do this, but some did. And Paul Dirac is one of those, you know, kind of the picture of the pure theorist who literally, I mean, looking at the math went, man, it's pretty weird that one of those numbers is negative. And everyone was like, don't worry about it. We just ignore the negative. And he went, what if we didn't ignore the negative? And sure enough, there's a particle. They discovered a particle because Paul Dirac looked at a piece of paper on his desk and said, I think there's a particle there. Now that actually sounds, again, completely hypothetically, like something a LLM could do. An LLM sitting at its virtual desk at a data center somewhere could look at a bunch of stuff and say, hey guys, what about that negative? And Paul Dirac was a huge part of the physics revolution of the early 20th century.

And so maybe our virtual Claude, Claude Dirac, will be a huge part of the incipient physics revolution of the 21st century. I hope my tone of voice conveys both that there are many reasons to be skeptical about that. At the same time, personally, I don't think it's like inconceivable to kind of put those things together and you say, well, it turns out that in human history, sometimes profound reasoners, you know, people or minds just with that ability to sit and think hard and kind of plow through assumptions about what is and what isn't have produced things that have been really important for humanity. I don't know. It could happen. So with that ambivalence, we kind of go full circle here, I actually do, where we begin, with that full ambivalence, that full sense of like, I don't know, that sounds pretty weird, but not impossible.

I'm just very curious to see what happens and what emerges over the next few years.

Part 16

Concluding Thoughts

Paul

Well, all right, last question. If you had a magic wand and could wave it at the industry to perhaps change the nature of how we're developing AI right now–something that either took the power away from big tech or changed the way that they interact with it. What is the more Sloan-esque approach to all of this?

Robin

This is, is probably not the best answer in terms of like bending the world in a better direction, but I know my answer instantly and powerfully. I would have them all reveal and continue to be completely transparent about all the training data. think there would, there would be a huge roster of what it is that that's going into these models. I think that right now it's, it's often obscured for both competitive and legal reasons, like we don't really know the copyright status of these of this stuff. And I think it really sucks. I really, really think it's important for end users of this stuff and important for policymakers. Again, I mean, to go back around to the commons, I think it's almost a form of respect for the stuff you're chomping on the stuff you're using to disclose what it is. And frankly, you should be proud of those things you're choosing, you should be able to stand by it, shouldn't be kind of hidden under a bucket in the corner of the room.

Paul

Yeah, I mean, it's not exactly the same thing, but I do always appreciate in Gemini and Perplexity both have done a pretty good job of like, here's what we're talking about when it makes a recommendation. It's sort of like highlighting a source. again, that speaks a little bit to the literacy of like this, but it's also type of trust and respect that this is not just a black box where that we figured this out. It's actually part of this large network.

Robin

Yeah. totally.

Paul

Well, Robin, thanks. This has been an amazing conversation as always. I could do this all day. So we really appreciate it.

Robin

This was fun! Yeah, me too, me too.

Thank you both for the invitation. It's really fun.

Kevin

Really good Robin thanks so much appreciate it